Minnesota’s latest economic outlook forecasts a jarring shift in the state’s finances: a healthy surplus over the next two years, and a nearly $3 billion shortfall soon after.

The swing comes from two forces moving in opposite directions. Spending, particularly on health and human services, is accelerating, while revenue is projected to slow significantly by the end of the decade.

MinnPost asked local economists for their thoughts on what’s driving those trends and how concerned the state should be about the projected budget imbalance.

Is this a short-term gap or a long-term problem?

A central question is whether Minnesota’s projected shortfall is tied to temporary shifts in the broader economy or baked in longer-term by unsustainable spending commitments.

“Structural means something that is likely to be persistent, long-lived,” said V.V. Chari, professor of economics at the University of Minnesota. “It’s associated with some fundamental changes in the way services are provided and money is spent.”

In Minnesota’s case, Chari sees unsustainable spending, much of which he attributes to the growth of new programs and expansions during the DFL’s 2023 trifecta, when the party controlled the governorship and both chambers of the Legislature.

“Spending is growing at more than twice the rate of revenue,” Chari said. “That’s the core problem. Almost all of it seems structural.”

He argues Minnesota has fallen out of the habit of evaluating programs, comparing them to results in other states, and adjusting accordingly, describing a failure to rigorously administer programs.

Related: Talking points for all. Amid wild federal uncertainty, here is what to know about Minnesota’s economic outlook.

“We used to do this really well,” he said. “But over the last seven, eight years, we’ve just stopped doing it.”

Ming Chien Lo, an associate professor of economics at Metropolitan State University, agrees the deficit is being driven “mostly” by structural, rather than cyclical, factors, though he sees legislative commitments rather than administrative lapses as the main driver.

Baseline spending means the cost of all programs and services as they currently exist under law, with no new legislation required to continue them. So if the Legislature did absolutely nothing, the state is legally obligated to continue funding programs like Medical Assistance, home- and community-based services, nursing home care, disability services, local government aid and K-12 education.

“Because the majority of state government spending is baseline (according to the law) while revenue is mixed, I interpret that deficits are mostly structural,” Lo said.

So Minnesota doesn’t need to vote to spend more than revenue in 2028-29. The system, left on autopilot, will do it unless lawmakers make policy changes.

Economists cited rapid cost growth in managed care rates, home care services, nursing homes, and care for disabled adults and children as some of the areas that are under the most visible fiscal pressure. Lo noted that federal data suggests the growth in health care spending is due not only to demographics but to “non-demographic” drivers — prices, utilization, staffing shortages and program design.

Medical Assistance, a joint federal-state program, is especially liable to swing in cost when prices or utilization change mid-year.

Related: In a K-shaped economy, is there anything Minnesota can do to bridge widening gaps?

The MMB forecast notes: “During calendar year 2024 and early 2025, health plans experienced higher-than-expected utilization and price of health care services. This resulted in two increases to 2025 rates in the middle of the calendar year.”

Those adjustments, which happen automatically, make planning difficult.

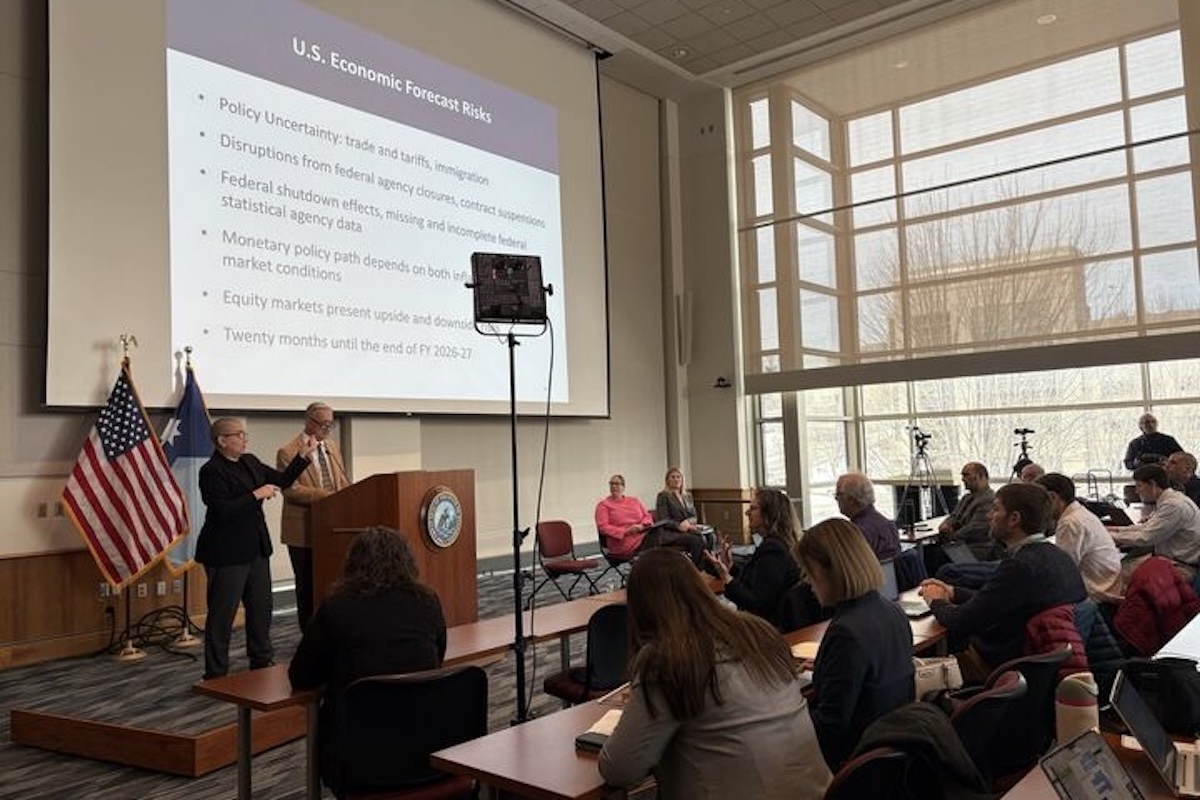

There’s even more assumptions and guesswork in projecting revenue, which depends both on policy, demographic and other trends the state can’t easily control.

State budget officials assume higher tariffs will redirect demand toward U.S. producers and that a “weaker dollar” will support exports beginning in 2026.

Lo and others question that logic.

“Tariffs may help some domestic producers, but consumers face higher prices and may cut spending elsewhere,” Lo said. “Would export gains via a weaker dollar overcome export losses due to possible trade retaliation? That’s not addressed.”

How concerned should we be about revenue projections?

Mario Solis-Garcia, professor of economics at Macalester College, went further, warning that the “extraordinary levels” of tariffs create corporate hesitation, investment delays and reduced hiring.

In addition to that, he raised an example not commonly discussed in budget analysis: skilled immigration restrictions.

“If the number of H-1B holders falls precipitously — arguably reducing the pool of highly qualified labor — what will be the impact over medium- and long-run growth?” he said.

Solis-Garcia argued more broadly that Minnesota’s forecasted deficit is largely a product of national policy risk spilling over into the state budget.

“Deceleration of the U.S. economy is a self-inflicted wound coming directly from Washington,” he said. “These changes may end up generating a temporary, not structural, problem.”

He pointed to high and unpredictable tariffs, uncertain immigration rules, efforts to weaken the Affordable Care Act and delayed and missing economic data as examples of federal problems that are now weighing on Minnesota’s economic outlook.

Related: How’s Minnesota’s economy? The answer depends on your income bracket

The effect of interrupted data flows, for example, has added to the uncertainty in the near-term and makes it difficult to definitively settle the debate over whether the medium-term imbalance will be enduring or temporary.

“We’ll never have an ‘official’ measure of unemployment for October,” Solis-Garcia wrote. “What these disruptions do is add a lot of noise to any forecast.”

The state’s Minnesota Management and Budget (MMB) effectively projected future revenue using second-quarter data while waiting for missing third-quarter results to arrive.

“While one can still generate forecasts (with older data), I wouldn’t put much faith in them,” Solis-Garcia said.

Related: Not just vibes: These economic indicators raise concerns about Minnesota’s economy

Aside from the fiscal questions raised by the budget forecast, several economists agreed that the likelihood of a recession seemed to be rising, though they cautioned it is difficult to predict when exactly it would land, if at all.

“For many of us, recession is only obvious once we are in it,” Lo said, noting that the volatility in the labor market, the stock market, and elsewhere would be noticeable, but difficult to forecast for.

“The risk of a recession will always be with us,” Solis-Garcia said.

“The question of whether the U.S. economy will enter a recession is not a matter of if but a matter of when,” he said. “And the signs seem to indicate that a recession in the coming months is more likely than not.”

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on MinnPost and was written by Shadi Bushra, MinnPost’s data journalist. It is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

MinnPost is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization whose mission is to provide high-quality journalism for people who care about Minnesota.